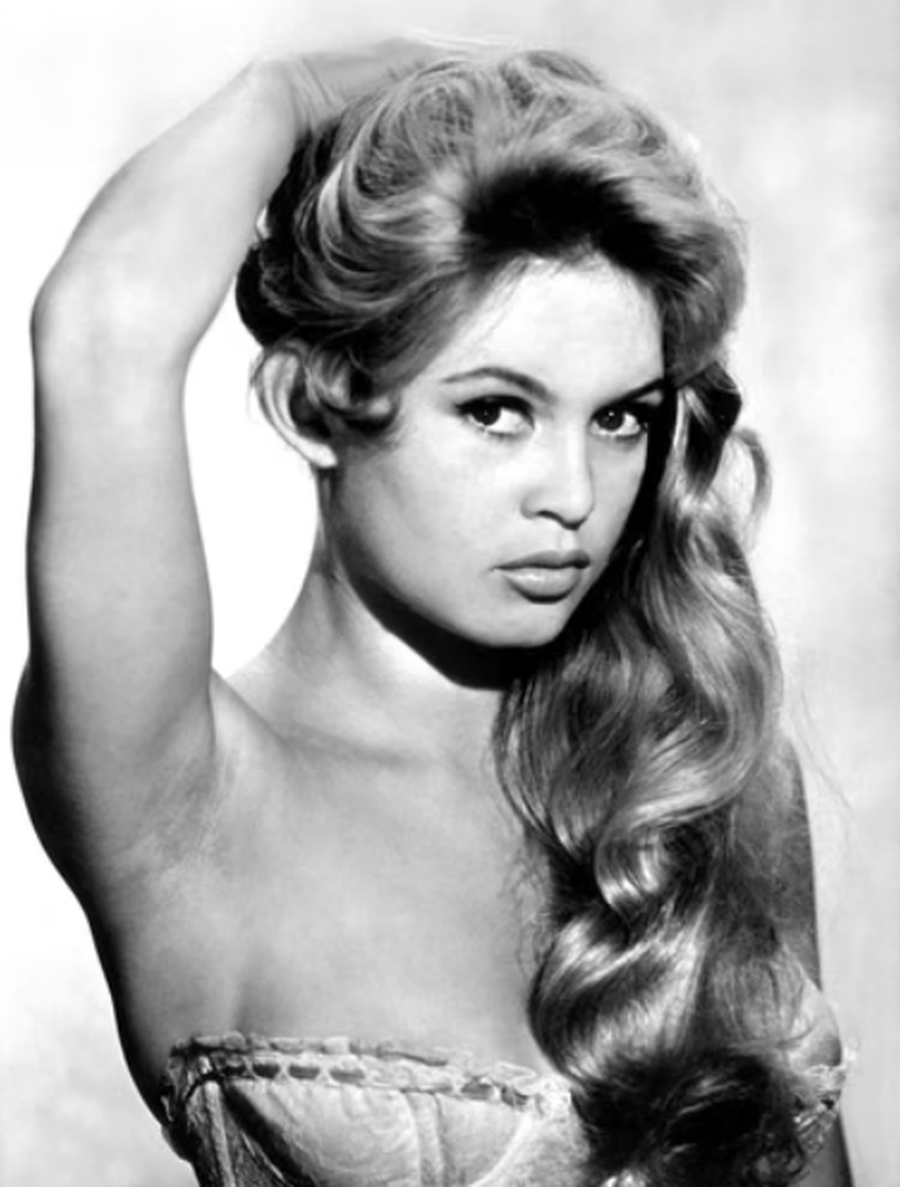

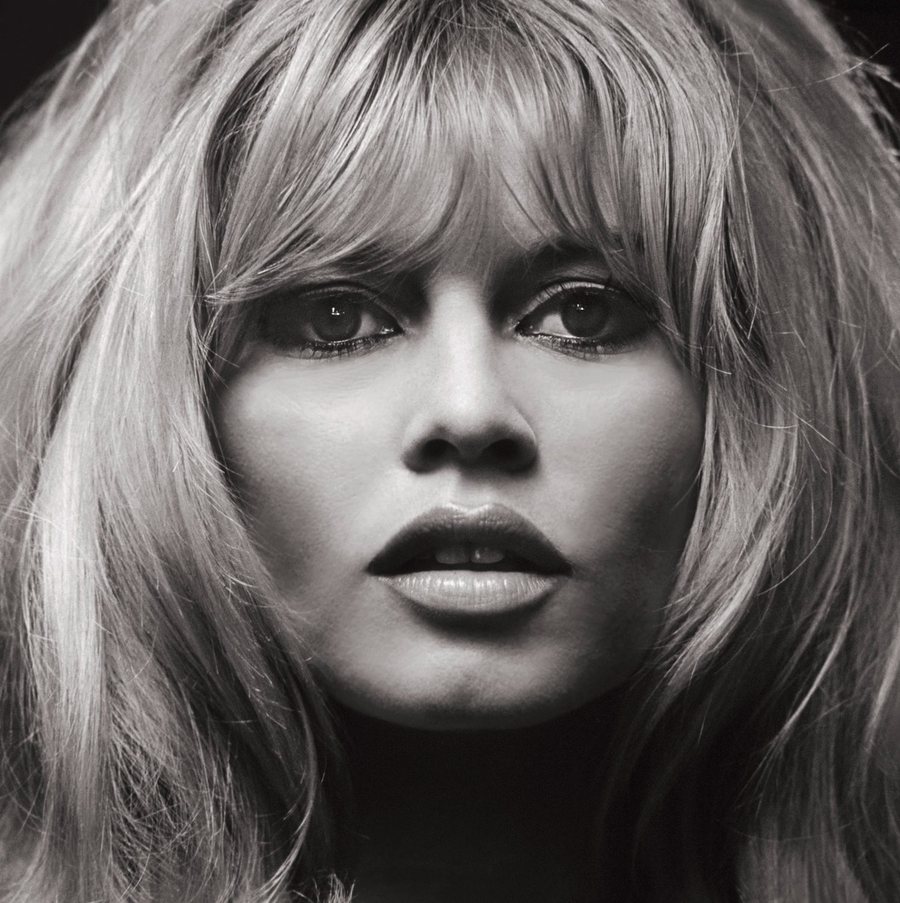

An icon for the fantasy of many men and women, a victim of ruthless media interference, an ardent defender of animals, but also a voice of racial hatred, with attitudes that became increasingly dark over the years.

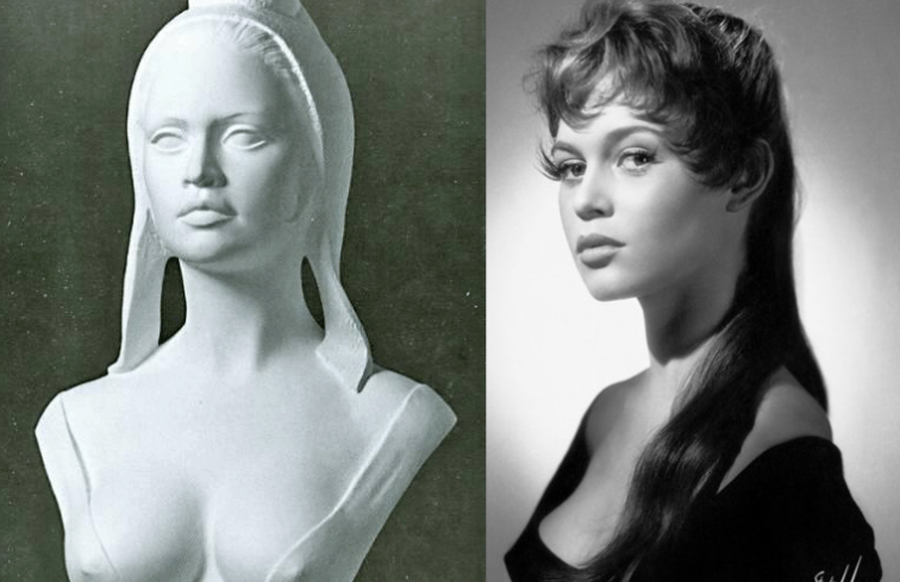

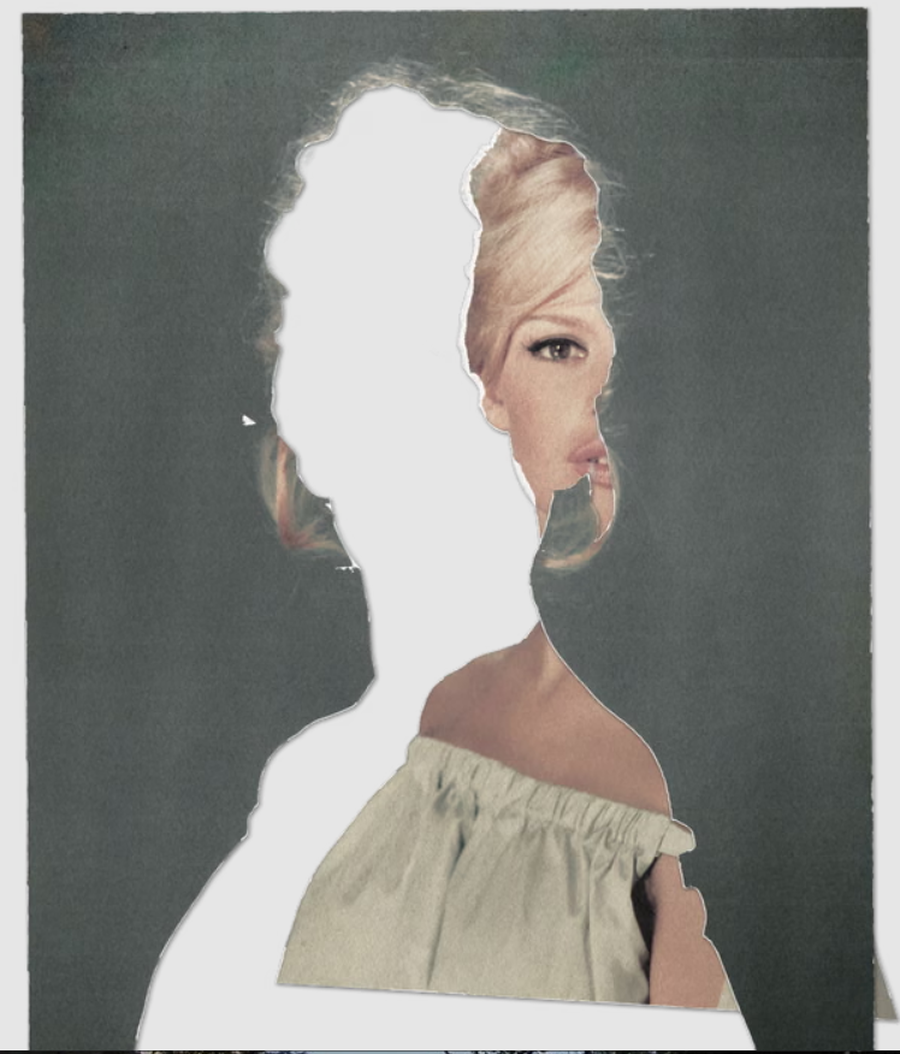

Brigitte Bardot has fueled the collective imagination for decades: from the erotic reveries of French cinema of the '50s and '60s, to the famous 1969 bust where Brigitte served as the model for Marianne, the symbol of the French Republic.

Marianne has been the national personification of the French Republic since the French Revolution, as an emblem of freedom, equality, and reason, as well as a portrayal of the Goddess of Liberty.

With her death on December 28, another illusion collapsed, this time of a younger generation. Singer Chappell Roan reacted to the news of Bardot's passing, at the age of 91, by posting a photo of herself at the height of her fame on Instagram, with her signature hair in a bun. "Rest in peace, Ms. Bardot."

The post was deleted just a day later. “Oh my God,” Roan wrote on Instagram Stories, “I didn’t know all that nonsense Ms. Bardot stood for. Of course I don’t support it. So disappointing to learn.”

Roan didn't specify what "insults" he was referring to, but there are many. Bardot's iconic image may have been frozen in time for some, but the reality was much harsher. Over the years, her public persona became increasingly toxic.

The late Bardot was, without a doubt, a dedicated animal rights activist. But she was also an unrestrained racist. Of Muslims, she wrote: “They slaughter women and children, our monks, our servants, our tourists and our sheep. One day they will slaughter us too and we will have deserved it.” Of illegal immigrants, she wrote that “they desecrate our churches, turn them into human stables, defecate behind the altar, urinate on the columns and spread their disgusting smell under the sacred arches.”

These stances didn’t just cost her her reputation: Bardot was convicted five times of inciting racial hatred. She called homosexuals “fairground monsters” and derided #MeToo victims as “hypocritical, ridiculous and useless.” However, after her death, French President Emmanuel Macron called her “the legend of the century,” saying that “Brigitte Bardot embodied a life of freedom.”

How can this paradox be reconciled: a woman who was both a symbol of sexual liberation and an outspoken voice of hate?

Në Francë, kjo anë e Bardot-it nuk ka qenë kurrë diçka e fshehtë. Nekrologjitë franceze kanë qenë të drejtpërdrejta. Ajo “mishëroi urrejtjen racore”, shkroi Le Monde, dhe ishte “një përjashtim në kulturën franceze, e vetmja figurë e famshme që mbrojti hapur të djathtën ekstreme”. Për më shumë se 30 vjet, Bardot ishte e martuar me Bernard d’Ormale, këshilltar i lartë i Jean-Marie Le Pen (themelues i partisë së ekstremit të djathtë, Fronti Kombëtar). Vetë Le Pen e përshkroi Bardot-in si “nostalgjike për një Francë të pastër”.

Edhe Libération vuri në dukje se dashuria e saj për kafshët u ndërthur me një vizion racist për Francën. Në vitet e fundit, Bardot jetonte e izoluar në Saint-Tropez, “e rrethuar nga kafshët dhe nga inati i saj”.

Sipas ekspertes së kinematografisë, Ginette Vincendeau, Bardot në Francë ka qenë gjithmonë më e pranishme politikisht sesa në Britani, ku ende shihej kryesisht si yll kinemaje. “Si pioniere në mënyrën se si u përfaqësua dëshira femërore, Bardot mbetet një figurë që meriton të analizohet dhe, në një farë mënyre, edhe të vlerësohet,” shprehet ajo.

Bardot nuk e quajti kurrë veten feministe, por ndikimi i saj në çlirimin seksual të grave në Francë ishte i jashtëzakonshëm. Në një shoqëri thellësisht konservatore, filmi “And God Created Woman” (1956), ku Bardot luante rolin e një gruaje që nis dhe e shijon seksin, pati një ndikim të jashtëzakonshëm. Ajo ishte e dëshiruar nga burrat, por edhe fantazi për gratë, sepse përfaqësonte një liri që shumica nuk e kishin.

“Me Brigitte Bardot, Franca kaloi nga një shoqëri e mbytur nga moralizmi te aspiratat që çuan në Majin ’68,” thotë historiania Émilie Giaime. “Ajo ishte karburanti i kësaj metamorfoze shoqërore.” Lëvizja studentore e majit 1968 në Francë filloi me protesta studentore kundër universiteteve të vjetëruara dhe autoritarizmit, duke u përshkallëzuar në demonstrata masive për ndryshime shoqërore dhe pothuajse duke rrëzuar qeverinë e presidentit Charles de Gaulle me trazira, barrikada dhe thirrje për revolucion.

Por fama e saj pati edhe një kosto të tmerrshme. Bardot ishte viktima e parë e kulturës së paparacëve. Ajo u përndoq pa pushim, deri në atë pikë sa u detyrua të lindte në shtëpi, e rrethuar nga fotografë, pas një shtatzënie që nuk e kishte dëshiruar dhe nuk kishte mundur ta ndërpriste. Pikërisht përvoja e saj ndikoi në krijimin e ligjeve të sotme strikte për privatësinë në Francë.

Ndryshe nga ikonat e tjera të epokës së saj, si Marilyn Monroe apo Jayne Mansfield, Bardot nuk vdiq e re. Ajo jetoi gjatë dhe u bë gjithnjë e më e inatosur.

“Kur e çmonton një mit,” thotë studiuesja Sarah Leahy, “kupton se është e pamundur të nxjerrësh një kuptim të vetëm nga jeta e një njeriu.” Simboli seksual, ikona e filmit, aktivistja, racistja. Brigitte Bardot ishte të gjitha këto njëkohësisht.

Source: Guardian