In recent years, the term “OCD” (and not only, but also other clinical terms such as “bipolar” or “narcissistic”) has become part of everyday vocabulary, especially on social networks. People use it easily, often to describe a tendency for order, cleanliness or when they want to show that they are attentive to details. “I'm a little OCD with my house”, “it has to be perfect because I have OCD”, are expressions that are easily said by those who are unaware of the weight that this word carries when uttered from the mouth of a person who actually lives with obsessive-compulsive disorder. What for some is a “quirk” or TikTok aesthetic is for someone else a daily mental prison.

OCD is not about order or cleanliness, it's about fear.

At its core, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is not about the desire for cleanliness or perfection. It is an anxiety disorder characterized by obsessions/fixations, unwanted thoughts, impulses, or images that invade consciousness and cause very high levels of anxiety, and compulsions, actions, or rituals that are performed to neutralize this anxiety. These actions can be visible (such as washing hands repeatedly) or mental (such as praying or counting to yourself).

OCD is not “cleanliness.” It is the constant fear that something terrible will happen if you don’t perform a certain ritual. A mind that can’t be stopped, that seeks absolute security where security doesn’t exist. Sufferers often describe it as an “endless emotional darkness,” a vicious cycle between anxiety and the effort to quell it.

But how does this disorder arise?

OCD is a complex disorder that stems from the interaction of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Studies point to a neurobiological imbalance in the fronto-striatal circuit, which is associated with impulse control and decision-making. Serotonin also plays a key role in modulating anxiety and compulsive behaviors.

But beyond the brain, there is also personal history, which often cannot be measured with MRI. OCD often develops after periods of chronic stress, traumatic events, losses or great responsibilities. In many cases, the individual has a perfectionist personality trait, with high moral sensitivity, a deep sense of responsibility that makes him experience guilt even for things that do not depend on him. OCD can be seen as a desperate attempt by the mind to regain control in a world that is perceived as dangerous or unsafe.

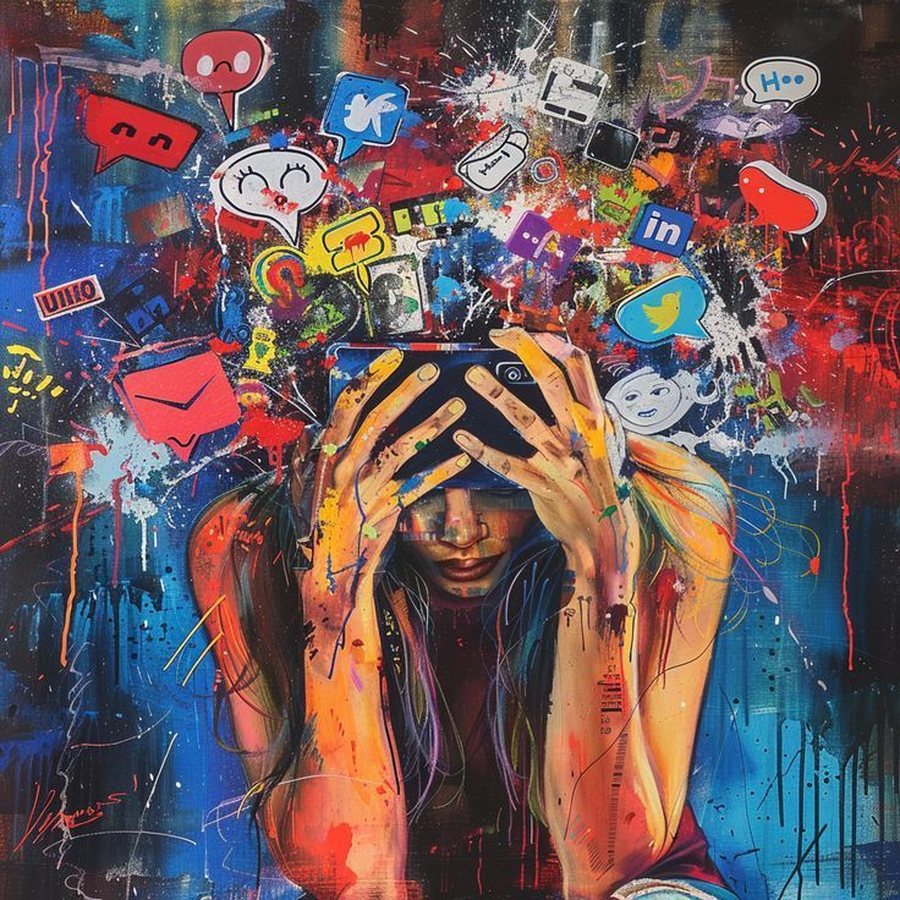

On platforms like TikTok and Instagram, the hashtag #OCD has millions of clicks. Videos with captions like “OCD aesthetic” show perfect desks, meticulously made beds, or synchronized colors. But this is a dangerous distortion. When a clinical disorder is presented as a form of “beautiful neuroticism,” a double distortion occurs: those who actually suffer from it feel more invisible while the general public learns a false version of the disorder.

This phenomenon of “romanticizing” OCD has direct consequences. First, it stigmatizes the suffering of people living with this disorder by making them feel misunderstood or even ashamed. Second, it harms awareness because it creates the perception that OCD is simply a way of being organized. And third, it contributes to the delay in seeking professional help because individuals who have real symptoms may think that they are not “bad enough” to have OCD simply because they do not fit the version they see online.

In clinical practice, OCD often manifests itself in ways that go beyond cleaning or orderliness. There are individuals who check dozens of times if the door is locked for fear that something terrible might happen. Others live with unwanted aggressive, sexual or blasphemous thoughts that terrify them by their very existence. There are patients who feel “unclean” not physically but morally, and therefore perform rituals to “cleanse” themselves mentally. There is nothing aesthetic about this, it is a daily struggle between reason and anxiety.

But why is it so easy to misunderstand OCD?

Because on the surface, OCD often masquerades as orderliness, punctuality, or “excessive care.” Society often glorifies these qualities. But what we see is only the outer layer, an attempt to keep something under control that is completely unstable inside. In fact, many people with OCD are acutely aware of the absurdity of their rituals but cannot stop. This is what makes the disorder so painful and exhausting: the conflict between awareness and fear.

Treating OCD requires care, patience, and a multifaceted professional approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is among the most effective therapeutic approaches because it helps the individual face their fear without resorting to rituals that temporarily extinguish it. But above all, treatment begins with awareness, the awareness that what they are experiencing is not simply “stress,” “perfectionism,” or “addiction.” It is a diagnosable and treatable disorder that deserves the seriousness and attention it deserves, not the banality of a hashtag.

In the end, we need to say it out loud: OCD is not a way to make life "more orderly" but a constant battle with the mind. And if each of us has any ethical duty, it is to not romanticize the pain but to help treat it.

In my clinical practice, I have seen people who have spent years hiding their rituals, not daring to tell others the fear that consumes them. And when they finally realize that what they have is not “madness” but a treatable disorder, it is often the first time they feel free.

And maybe this is the message we should spread instead of turning it into a trend: that behind every unwanted thought there is a person who is trying with all his might not to lose control of himself, and this is not a trend, it is courage.

By Ilva Mile, Licensed Clinical Psychologist.