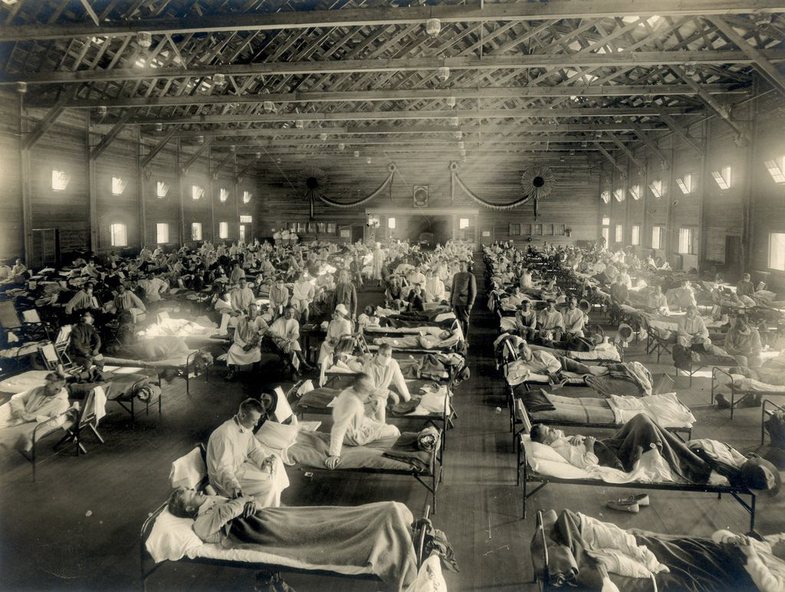

After World War I, a flu pandemic invaded the world and killed at least 50 million people. What can we learn from the Spanish flu to use during this pandemic?

One hundred years ago, the world was recovering from a war that claimed 20 million lives and suddenly had to face an even more deadly threat: a flu pandemic.

The pandemic, which was known as the Spanish flu, is believed to have started at army training camps on the Western Front. The unsanitary conditions - especially in the trenches on the French border - helped incubate and spread the virus. The war ended in November 1928, but as the soldiers returned home, virus carriers were causing an unpredictable tragedy; about 50-100 million people lost their lives.

The world has gone through several pandemics since then, but none have been as deadly or as widespread.

At this point, the world is facing another pandemic - Covid-19 - so let's look at what we've learned from one of the most devastating diseases in history.

Pneumonia is deadly

Most people who die from Covid-19 go through a form of pneumonia that is amplified as the immune system is weakened by the virus

This is one in common with the Spanish flu - although the mortality of Covid-19 is many times lower. Older people and those with immune problems - which make up the majority of victims of the disease - are more prone to infections that cause pneumonia.

Places that escaped danger

When the Spanish flu struck, aviation was one of its beginnings. But only a few places in the world escaped horror. The spread was slower as it passed by the passengers of the railway lines. Some countries in the world were affected months or even years later by Europe.

Some specific communities have managed to completely avoid the flu through basic techniques still used today. In Alaska, a community in Bristol Bay, no one was affected. They closed schools, stopped public gatherings, and barred entry into the village. It was a simple version of the restrictions that apply today in northern Italy and in Hubei province in China.

Doctors have labeled the Spanish flu as "the largest medical holocaust in history." Not just because it killed a lot of people, but because most of the victims were young and healthy. Usually, a healthy immune system can withstand the flu without problems, but this version hit so fast that the body could not cope and triggered a massive reaction known as the cytokine storm; the lungs were filled with fluid and returned to ideal sites for secondary infections. The older people, surprisingly, were not very vulnerable. Probably because they survived a similar version of the flu in the 1830s.

Public health is the best protection

The Spanish flu occurred shortly after a world war and most of the proceeds went to the military. The idea of a health system was in its infancy - in many places only the middle class or the wealthy could afford a doctor visit. The flu killed poor and unfortunate people, poor nutrition, poor hygiene, and other health problems.

It was the Spanish flu that prompted the development of a health system in developed countries, as scientists and governments realized that pandemics could spread faster than before.

One-on-one treatment of patients is not enough - to cope with a pandemic nowadays, governments must use resources as if they were at war, quarantine the sick and limit the movement of people.

The measures being taken today to control the spread of coronavirus worldwide are a consequence and lesson of the Spanish flu.

Source: BBC Future